In lay conversations surrounding the state of a society, sport is often relegated to the margins. Indeed, we are more likely to describe societies in the context of their politics, economy, geography, language, before we discuss the sporting culture thereof. Yet, all things considered, this second-tier status is an unjust reflection on the societal impact of sports even on the grandest scale! For example, the evolution of Black civil rights in the USA owe is in complete without the groundbreaking work of boxer Jack Johnson, Jackie Robinson, Tommie Smith and John Carlos as it is without Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr, and Malcolm X. In 1969, El Salvador and Honduras engaged in a two-week war sparked by the latter’s defeat during a World Cup qualifying match. These two examples just reiterate how sports either provide a window into societal issues or become the very battleground upon which said issues are addressed.

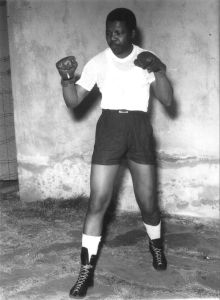

Modern South Africa’s troubled history isn’t exempt from a distinct narrative that can be told through sports. From the onset, the European settlers viewed sport as critical to their ‘civilizing mission.’ Consider, for example, the case of the Orange Free State Football Association, an-all Black South African team that traveled to Britain in 1899 ‘to show the British public how far they are advanced in the beloved game of ‘soccer’ football.’ (Odendaal, P18.) Sport thus became a status symbol in which proximity to ‘whiteness’ in comportment was desirable. It is then no surprise that such prominent figures in the Black community as Sol Plaatjie and Nelson Mandela developed a reputation in cricket and boxing respectively in the earlier part of the 20th century.

That sport had layered socio-political implications is, as we established in the beginning, a phenomenon not particularly unique or definitive to South Africa. What is interesting, however, is how this larger-than-life unifying force became to one of the defining pillars of the Apartheid philosophy. In ‘Sport and Apartheid’ Merrett explains at length how such sport segregation, supported by such legislation as the Group Areas Act and Urban Areas Act, served to patch the divide between the British and the Boer by pushing for a nationalistic White agenda in opposition to the Black Africans (Merrett, p1.) From the implementation of Apartheid in 1948 until 1967, the notion that there would be no racial mixing was reinforced time and again, with one member of parliament going as far as describing the ‘international recognition of non-racial sport as a declaration of war’ Merrett, P2.) So committed was the Apartheid regime to maintaining their racist status qu0- even in sport- that they were willing to risk global isolation! It was not until 1967, under the Vorster regime, that South Africa began to loosen its stance against multi-racialism in sport. If for nothing else, Vorster was committed to reintegrating South Africa into the global community through sports.

Despite progress in this regard, as evidenced by 1971 unveiling of the policy of multi-nationalism in sport as well as mixed football being included in the 1973 South African Games, the rest of the world was not immediately won over. In just about every other sector of society, Apartheid’s ugly policies reigned supreme and the international community reasoned that ‘reform in the area of sport was unacceptable without more fundamental political change’ (Merrett, p7.) Even if sports itself was largely free from the clamping jaws of segregationist policies, it was still indirectly subjected to them through school segregation which meant Black African students still had no access to the educational resources that may have privileged certain sports. As such, the rest of the world held fast to its isolation of South Africa- sports and across the board. It was not until the 1990s, with pending and subsequent independence that the country was reintegrated into the global sporting arena.

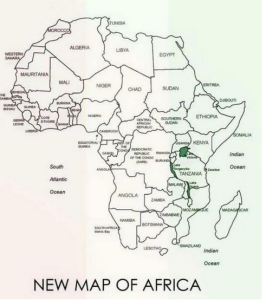

From where we stand, there are several critical take-aways from the readings on Apartheid-era sport. Recently, South Africa has been dogged with xenophobic attacks especially targeting groups of African immigrants. At first glance, this seems bizarre, given the rich heritage of Pan-African nationalism in the country and the efforts of their African neighbors in the fight against apartheid. However, three factors- all touched on in ‘Sport and Apartheid’ play a huge role in these ‘Afrophobic attacks.’ First, Merrett described the segregation as emphasizing ‘the otherness of Black South Africans, but also encouraged their polarization one from another.” Thus, due to seeds planted by Apartheid, Black South Africa inherited a heightened sense of tribalism, and xenophobia against African immigrants is a descendant of aforementioned culture. Secondly, decades of isolation from the international system may have skewed the skewed the citizens’ perception of their place on the international scene, thus creating a sense of South African exceptionalism. I spoke to an uncle who is from Zimbabwe but has lived in South Africa for the past 20 years, and he explained how, on several occasions, Black South Africans would say to him “Wena muAfrican?’ (‘You are an African’- unlike them, South Africans’) Finally, the Apartheid machine that kept Black Africans out of places of opportunity- both literally and figuratively- has largely been maintained, despite the end of Apartheid. Many of the schools remain segregated, the Black Africans still largely live in the townships designated by the Group Areas and Native Land Acts, and the economy remains very much in the hands of the white South Africans. The xenophobic attacks may be misguided, but they have been born largely out of the economic frustration of poor Black South Africans remnant of Apartheid era socio-politics.

it is also worth doing that we draw parallels between segregated South Africa and Jim Crow USA. Indeed, some pundits have described the two countries as ‘long lost cousins’ in their treatment of their Black population (Attrige, 1998, P227.) Let us take a quick moment to break down one short verse from Merrett.

- ‘the emergence of a Black sporting hero could have challenged and undermined the fundamental beliefs required to sustain apartheid ideology”- similar conversations around white supremacy occurred around Jackie Robinson and Jack Johnson

- “Sportspersons who questioned white hegemony were labelled agitators and subversives”- Mohammed Ali comes to mind.

Thus, the idea of using sport to enforce racial separation, and the fear of the reverse in the mind of racial perpetrators, are both an unoriginal concept and a ubiquitous one.

The issue of xenophobic violence in South Africa is troubling to its neighbors; to the point when other countries, like Malawi, repatriate its citizens residing in South Africa for their own safety. A three-pronged approach to that issue rightly describes the complexity and irony of the issue. One possible cause you mention is the international isolation imposed on South Africa has created an identity rift between black South Africans and those of other African countries. It makes sense that the feeling of “otherness” that was imposed upon black South Africans by whites could then be shifted onto other Africans. I believe that the exceptionalism in South Africa is a product of poor economic progress and the legacy of Apartheid. You mention that the “Apartheid Machine” has not been dismantled, and is still shutting blacks out from economic growth and opportunity. South Africa is one of biggest economies in Africa, but has wide spread poverty. It is easy to see where the economic frustrations of black South Africans can be misdirected to other Africans who they may view as “stealing” opportunity. It seems like a microcosm of what happens in countries who are experiencing recessions, which then tend to become less migrant-friendly.

LikeLike

I absolutely agree with the parallels you draw between Apartheid South Africa and Jim Crow America; the similarities in the institutionalization of racism and oppression are undeniable.

You discuss modern South African xenophobia, and trace the roots of recent violence back to the racial distortions created by the apartheid-era government. America, too, is struggling with racially-based violence in the modern era: we are struggling to make sense of our identities and our communities in the wake of highly-publicized police brutality and murder, and the resulting riots in Ferguson and elsewhere. Although the discord isn’t xenophobic, I think it still reveals the lingering trauma of Jim Crow and racial abuse. I wonder if it is possible to fully heal from decades of profound injustice, and what that process might take to be successful.

LikeLike

I find your comparison of Apartheid South Africa and Jim Crow Southern United States to be enlightening and yet slightly doctored for the sake of comparison. While I agree that the racial abuse and laws of segregation were both highly volatile with societal ramifications in both countries; it is unmistakable to forgo mention that while South Africa was excluded from international sporting, the United States of America was a welcome and hallowed Olympic and World Cup participant. The United States earned their only podium finish in the 1930 World Cup, winning the bronze medal that year. 1930 was a very different time from the 1960s, but race relations in the United States at the time were tumultuous at best. I believe it is only for the reason that South African Apartheid law lasted far longer than American Jim Crow that South Africa was treated to exclusion on the international sports stage. Cultural change in the globalizing world around us lead to a more critical view of racist regimes; Jim Crow laws were created and eradicated just prior to total globalization, Apartheid reigned in South Africa until the 1990s. It is worth mention that South Africa was also excluded from the global political world in addition to the global sporting world. South Africa was not invited to be a part of the United Nations Security Council until just a few years ago and even still is fighting for more than just a rotating seat at the UNSC. I wholeheartedly agree that Apartheid and Jim Crow come from the same xenophobia and hatred, lead to the same societal ramifications and distrust between Whites and Blacks in both countries, but I believe the similarities in their global ramifications end there.

LikeLike

You are spot on factually!

My post speaks parallels more the nature of discriminatory culture in the two countries than it does the global ramifications. Global Ramifications (or any ramifications for that matter) are a function of time, environment etc, but don’t always correlate to the nature of the beast they are reacting to. (For example, two people can do the exact same thing, and because they’re in different places- or simply that they are perceived differently- be subject to different ramifications!)

That said, indeed, for several reasons, Apartheid and Jim Crow were not met with the same reactions globally, but that says more about the other factors determining ramification than they do about how similar the two were.

LikeLike

You are so right in emphasizing the significance of sport to societal conditions and the parallels o f Apartheid South Africa and Jim Crow America. Sport definitely has been used to advance racial supremacy, political ideals and even as a platform for fighting such oppressions. Another example in American history that comes to mind is the Black Power Salute in the 1968 Olympics. In light of the Civil Rights Era, the two African-American athletes on the Olympic podium was such a powerful statement. Throwing their fists in the air was an extreme statement against their own country. It was as if they were representing a different side of America. They used this major sporting event as a platform to advocate for African-American citizens across the nation, whose voices and experiences were unheard in the international sphere.

LikeLike